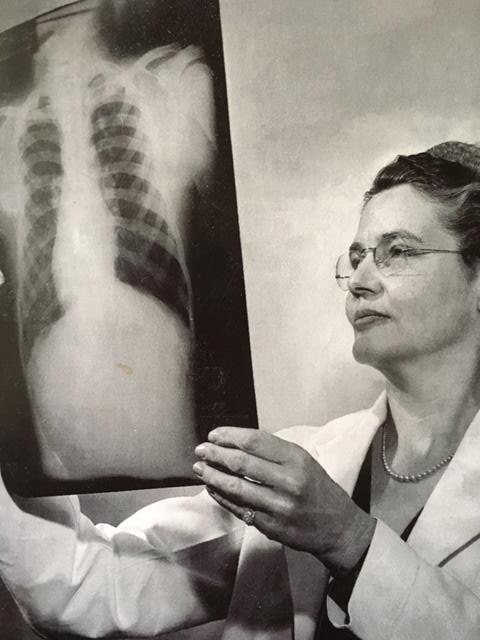

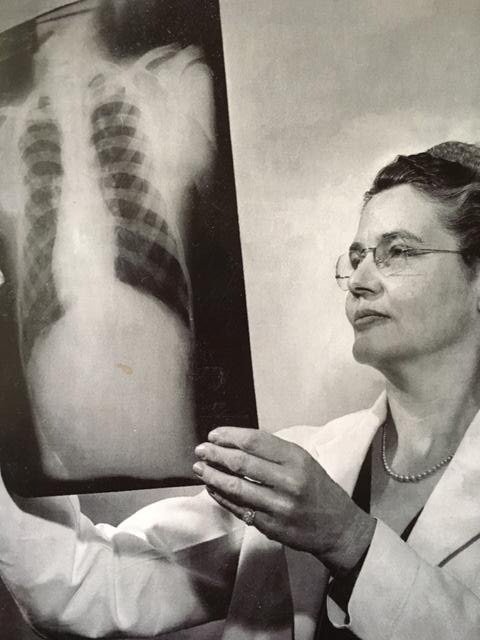

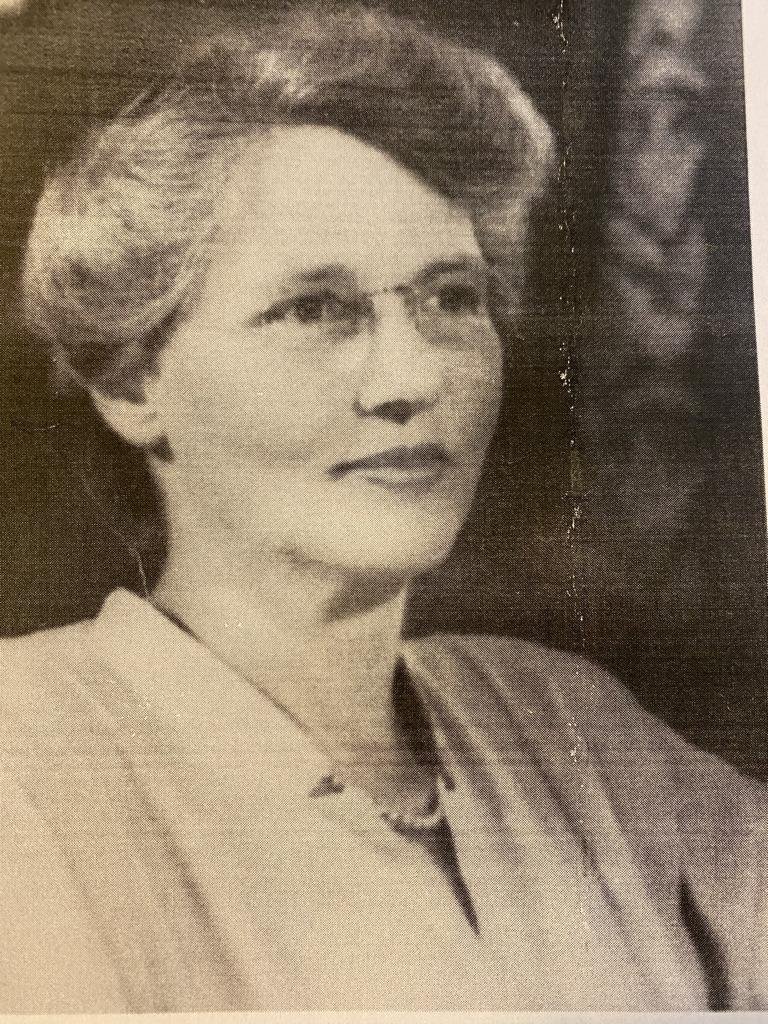

Helen B. Taussig, MD

About Helen

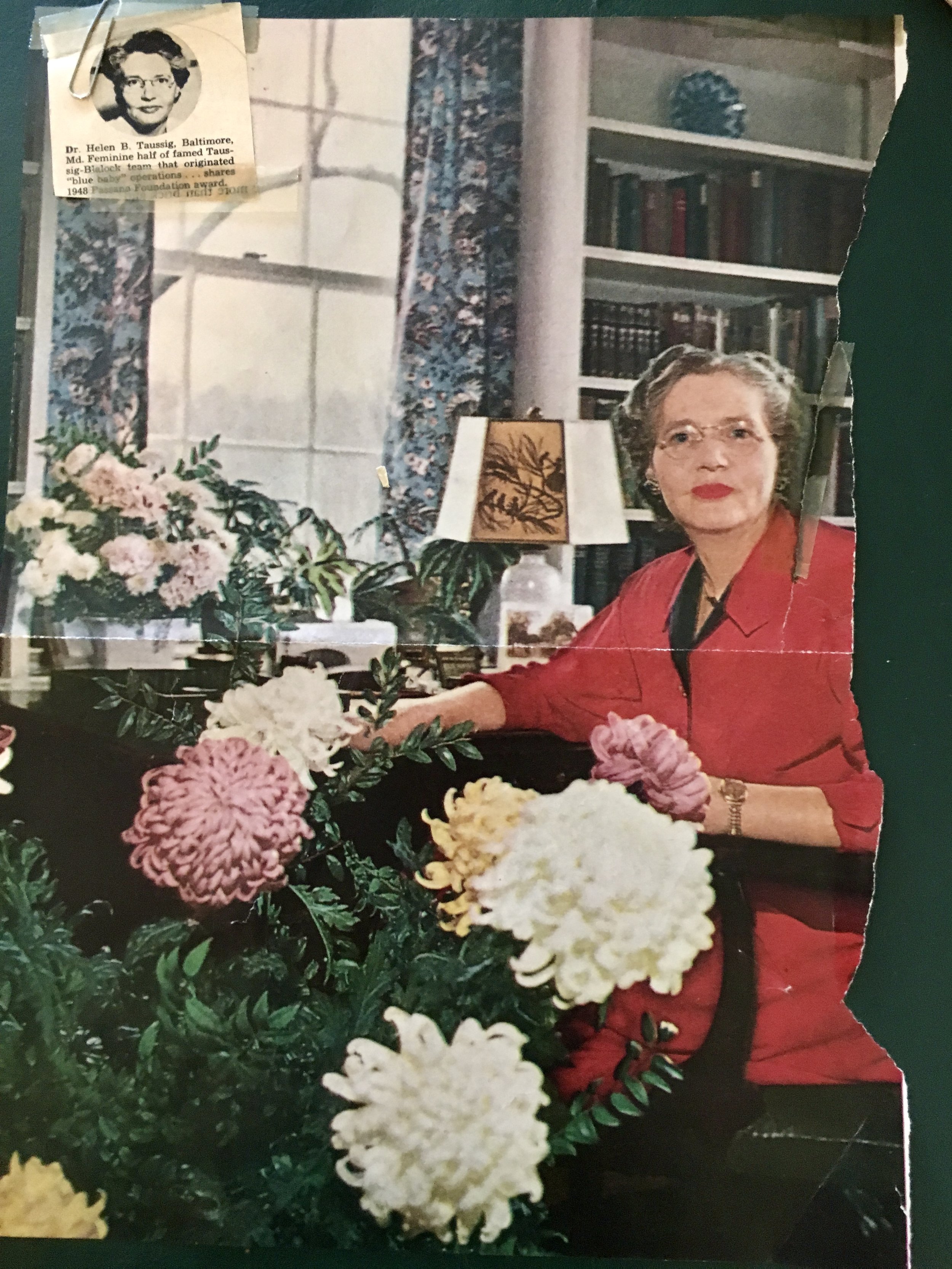

An elegant, indefatigable woman in a man’s world, Helen Brooke Taussig (1898-1986) was a children’s doctor whose discoveries in a humble Baltimore clinic saved lives and helped start modern heart surgery. She was also one of the 20th century’s foremost patient advocates.

Helen’s life unfolded amid two world wars, the rheumatic fever era, and the rise of data and technology to replace the doctor’s touch. Unable to enroll at Harvard University because she was a woman, she left her beloved family in Boston in 1924 to study at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, one of the few science-oriented medical schools that admitted women. Blocked from opportunities to treat adults with heart problems, she agreed to lead a new children’s heart clinic knowing there was no treatment, and many children died. With scant help or money, Helen struggled to devise ways to prevent rheumatic fever patients from developing fatal heart damage and to ease the final days of babies born with heart defects. The suffering she witnessed hardened her resolve to help her patients.

Within five years Helen became the first to diagnose a specific congenital heart defect in a living child, making it possible to fix. After observing children with flawed hearts for more than a decade and learning why some survived longer than others, Helen convinced a surgeon, Alfred Blalock, to reroute blood vessels in a tiny infant in the hope of increasing her oxygen. The baby lived. News of “miracle babies” – breathless, lethargic children with blue skin who turned pink after this new surgery and rose from their hospital beds – circled the globe, followed by an explosion in vascular surgery and ultimately, surgery on the heart itself.

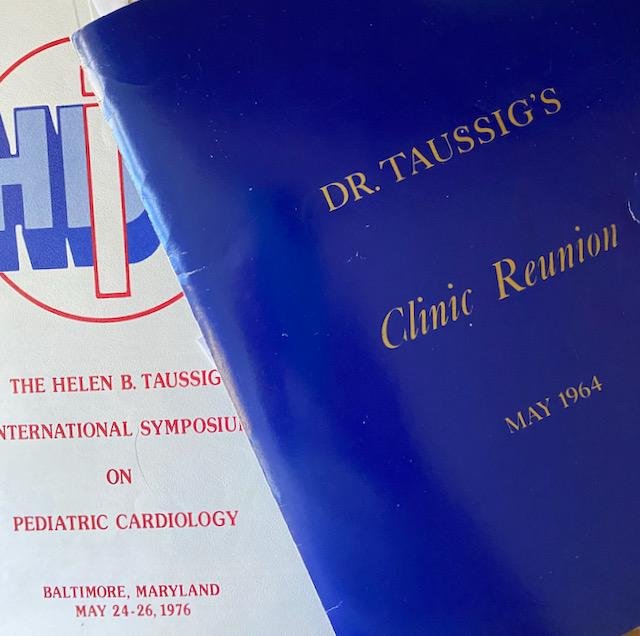

Helen followed her patients into the operating room and throughout their lives, in the earliest studies to assess treatments and quality of life. As post-war medicine exploded, she emerged as a formidable critic of unnecessary or ill-timed surgery and invasive treatments by doctors who knew little about defective hearts or developing children. With grace, tenacity, and data, she disarmed hostile colleagues who resented her fame and sway over patients. She trained an international cadre of doctors in her methods and set the standard for a new branch of medicine, pediatric cardiology.

Her endless pursuit of the cause of her patients’ suffering led Helen to Europe in 1962 to investigate the link between birth defects in babies and the popular sleeping pill thalidomide. She returned with a notebook of evidence and photos of maimed babies to wage a campaign that galvanized the public and tipped the balance in Congress in favor of passing US drug testing regulations, still the toughest in the world.

Her personal battles were as daunting as her professional ones. They included the loss of her hearing in 1930 just as she began to distinguish the sounds of diseased and defective hearts. As stethoscopes proliferated, Helen achieved renown as a master diagnostician the old-fashioned way, by listening to heart sounds with her hands on a bare chest.

The most prominent woman physician of her day, courted by media and politicians and honored by patients, Helen was known for her fearlessness as well as her humility. A daughter of privilege, she was as comfortable in a tent on her lawn as she was at the Hotel de Crillon in Paris, where she stayed when she received France’s highest civilian award. Just as she looked to the body’s natural healing processes for clues to help patients, Helen sought inspiration and sustenance in the natural world for herself. The gardens she created on her Baltimore property with help from doctors she trained reflect her vision and hope.

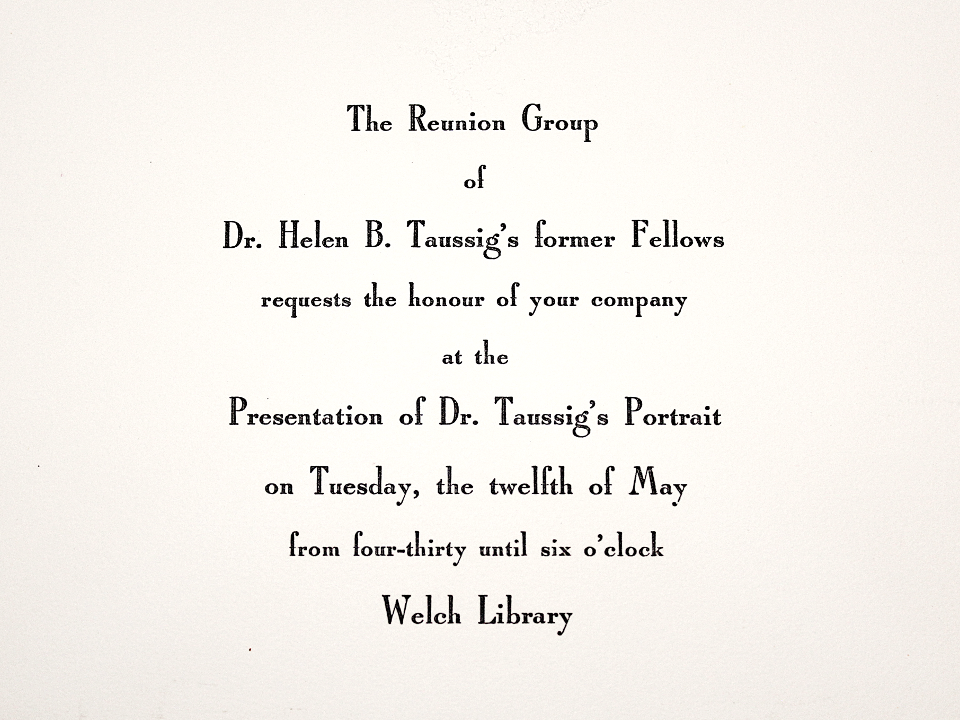

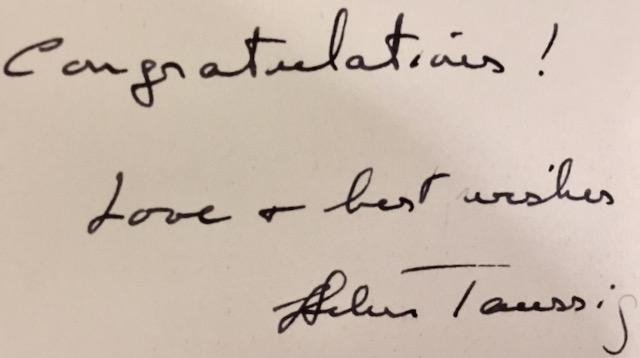

Her followers fought for decades over a worthy portrait by which to memorialize Helen. Today this woman with piercing blue eyes and gentle touch is remembered as much for her scientific discoveries as for her battle against unnecessary suffering.

Frequently Asked Questions

Check back soon!

Photos of Helen

Memorabilia

Her Work Continues…

Tell me your stories about Helen, blue babies, and medicine (information will not be used without permission).

Additional Reading

Article: Helen B. Taussig, MD, 1898-1986

Article: The Changing Face of A Strong Woman