This time of year, as children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig prepared to join her family in Boston, her Baltimore living room windows and walls would be decorated with strings of glittery Christmas cards and photos from her patients.

They were her real family, Helen’s niece, Polly, told me.

Like most women doctors in her era, Helen chose not to marry. She wrote that while she didn’t have the satisfaction of raising children of her own, she was blessed with a multitude of nieces and nephews. She saw them mainly in summer, though, at the family’s home on Cape Cod. Helen had to leave her beloved family to study at the Johns Hopkins school of medicine, one of few science-oriented schools to accept women, and stayed in Baltimore for the one job offer that allowed her to treat patients.

Except for 1930, the year she came down with chicken pox and admitted herself to the infectious diseases ward in the children’s hospital, Helen always returned to her family in Boston for Christmas.

“I had a lovely Christmas with my two sisters,” she wrote a friend after one visit. “My sister Mary had real candles on her tree! Oh – I’d forgotten how lovely they were and what a different feel they give one – the true meaning of Christmas swept back over me – and of course, for both of us – the Christmas of our childhood.”

Light illuminates the darkest corner, so I suspect she meant hope, the theme of A Heart Afire, my newly released biography of Helen. The renewed hope that accompanies a birth. Without hope, there can be no change. Helen called it imagination, which when accompanied by a strategy and hard work leads to advances in science and art and I will add, politics. This was a paraphrase of one of her heroes, Ralph Waldo Emerson. The German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of my heroes, called it optimism even in the face of overwhelming darkness, a feeling of not wanting the other guy to win that inspires you to act no matter the odds. He was executed in a Nazi prison for his part in an attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler. He explains in Letters and Papers from Prison, but this time of year, I dip into his Christmas Sermons.

Helen took a job that no male classmate wanted, studying children destined to die from heart damage. Even women colleagues worried she was wasting her time. She never gave up. Like Emerson, she renewed her spirit by walking the woods near her house and observing nature. As she wrote in the 1960s to a grieving mother, it was by studying and re-studying the problems of dying children that “we learned to help so many.”

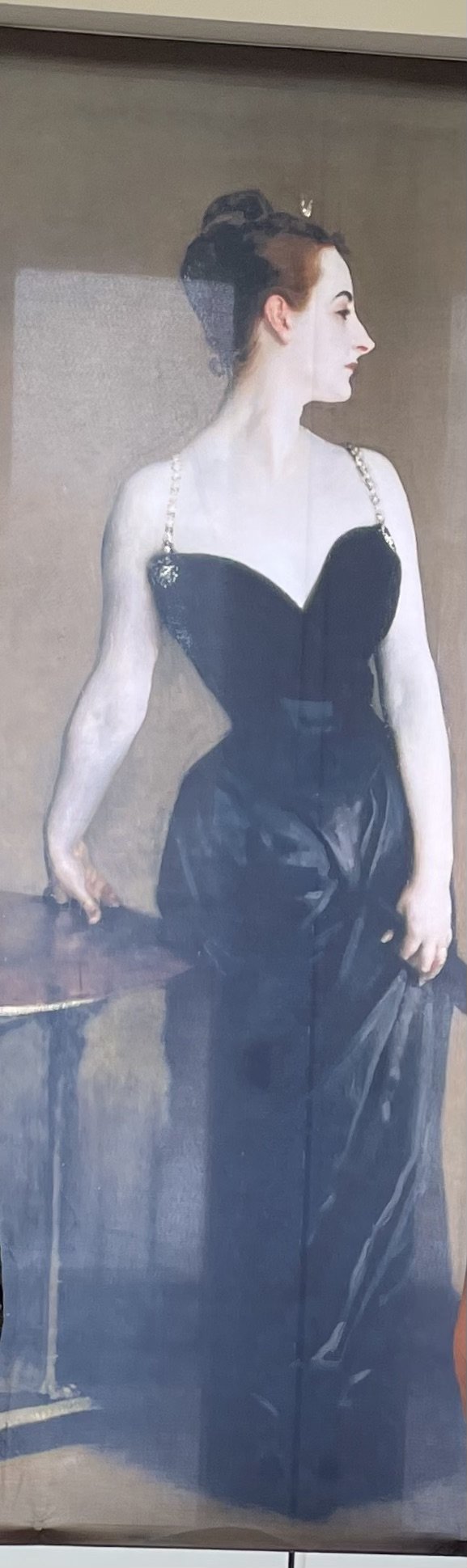

Helen’s grandniece Mary sent me this old photo of a family dinner, possibly Thanksgiving or Christmas. Helen is far right, looking elegant as usual.