Barbara Moreland, a cheery grandmother who runs her husband Gary’s plumbing business in rural West Virginia, still has the patient wrist band she wore in 1965 when surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital fixed her flawed heart.

Read more

Your Custom Text Here

Barbara Moreland, a cheery grandmother who runs her husband Gary’s plumbing business in rural West Virginia, still has the patient wrist band she wore in 1965 when surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital fixed her flawed heart.

Read more

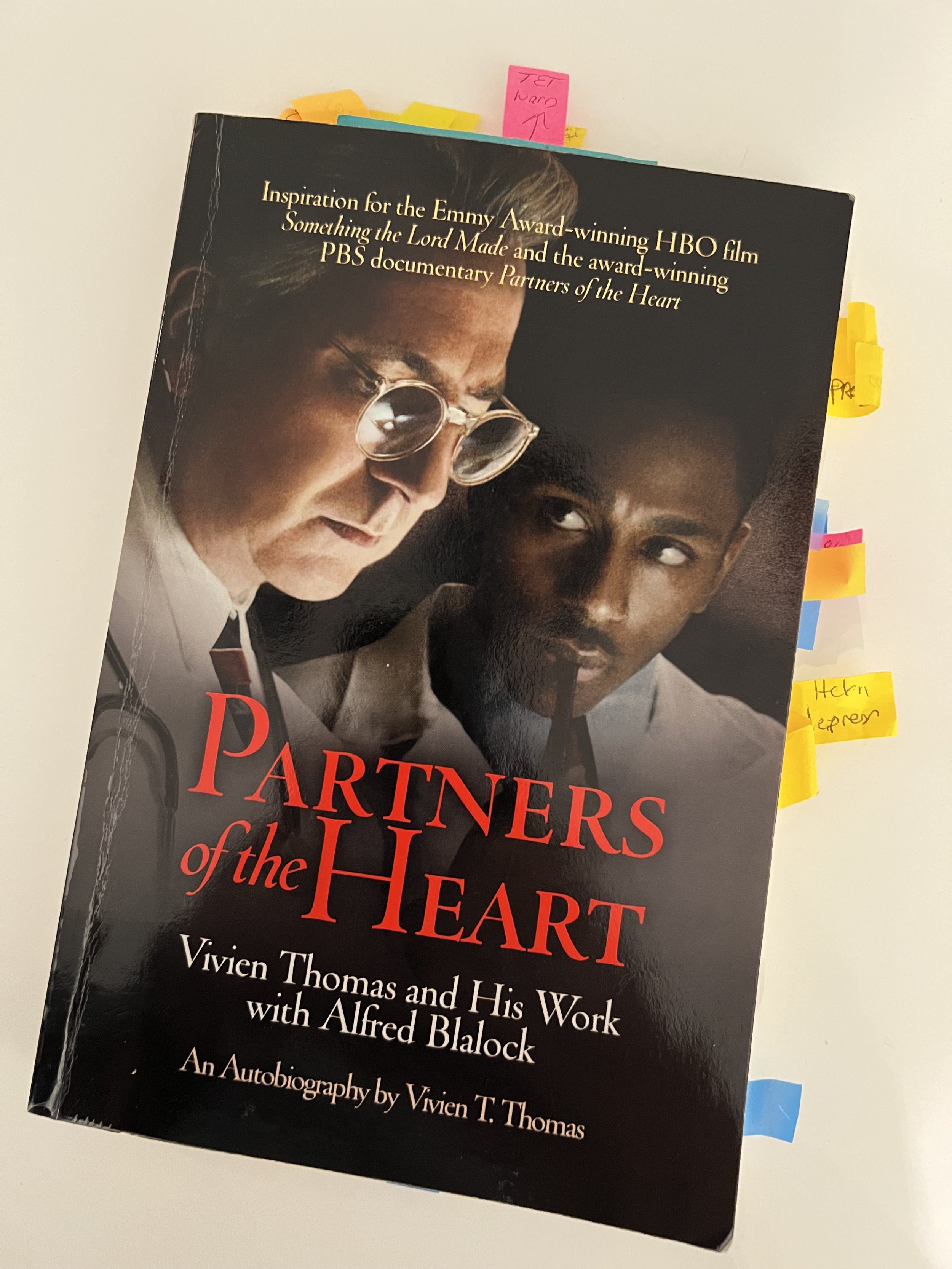

Thanks to a December Baltimore Banner article by Leslie Gray Streeter about the popularity on TikTok and YouTube of Vivien Thomas, the self-taught pioneering African American surgeon, Baltimoreans are discovering and re-discovering the 2004 HBO movie about his life, Something the Lord Made.

A friend who saw the movie for the first time asked if I had known of it, since my book, A Heart Afire, a biography of the pediatrician Helen Brooke Taussig, details some of Thomas’s work at Johns Hopkins hospital with the surgeon Alfred Blalock to develop lifesaving heart surgery for her patients.

Yes! The movie was based in part on Thomas’s 1985 memoire, a source I consulted to learn about the surgery and Helen’s role in it. It’s an eclectic take on history: blow-by-blow details of laboratory experiments and techniques, chatty sketches of famous surgeons, and straightforward tales of indignities suffered by a self-made Black man.

It was a book Thomas never expected to write. A publisher was hard to find. And with the original title of Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery, the audience was limited.

How did Vivien Thomas win his place in history and popular culture?

e.

A top surgeon at Hopkins realized the importance and extent of Vivien Thomas’s work while researching Blalock’s life and pushed Thomas to write his autobiography. Mark M. Ravitch, an outsized personality who helped develop pediatric surgery, kept after Thomas for nearly two decades after learning, to his surprise, that Blalock delegated his experimental work on the nature of traumatic shock to Thomas and a surgical resident. At the time, it was customary for surgeons to perform their own experiments. Neither Thomas’s name nor his contribution was noted on papers Blalock wrote about his pioneering discovery, which made surgery safer.

Ravitch was also chagrinned to learn that he himself mistakenly credited another surgeon, C. Rollins Hanlon, with an innovative surgery Thomas developed. This was first surgical treatment to help children born with their major arteries reversed (transposition of the great arteries). Hanlon and Blalock are listed as authors on the 1948 paper describing it. Thomas had embarked on his solution for this condition secretly, testing it again and again in dogs before unveiling it to Blalock. (Usually, Blalock directed and the two improved on the idea.) When he showed Blalock the opening he created between the upper heart and a pulmonary vein — a new path that allowed oxygenated blood to flow into the body — Blalock reacted with disbelief. It looks “like something the Lord made,” Blalock said. (Hanlon also played a key role in this surgery; his refinements dramatically reduced mortality.)

While Thomas worked a second job tending bar to pay his bills and wondered whether his life story was worth telling, Ravitch and other surgeons in Blalock’s famed training program – many of whom learned to operate in Thomas’s dog lab -- commissioned a portrait of him to hang in the medical school. It was unveiled in 1971. In 1976, Hopkins awarded him an honorary degree and made him an official member of the faculty.

After he retired in 1979, Thomas began writing his account longhand using his extensive lab records. Ravitch pushed Thomas to provide more detail about the people he named and his own impressions. Thomas added this without judgment. (In one memorable scene, Thomas prepared to quit after Blalock angrily dressed him down, leading Blalock to promise never again to speak to Thomas in raised voice.)

To help with what an ailing Thomas called his “production problem,” Ravitch assembled and ordered Thomas’s chapters and handwritten scenes, and wrote the index. A few days before his book was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in December 1985, Thomas died. Ravitch went into high gear, pitching the memoire with ferocity, as is evident from Ravitch’s papers archived at the National Library of Medicine. He mailed the book or letters about it to everyone on his Rolodex (he was a past president of the American Surgical Association.) It was his colleague Judson G. Randolph, a George Washington University surgeon, chief of Washington’s Children’s Hospital, and Ravitch’s co-author on a pediatric surgery textbook, who told writer Katie McCabe about Thomas.

McCabe tried for four years to sell a story about Thomas before Washingtonian published it in 1989. By then, Ravitch was dead. Her article won the 1990 National Magazine Award and admiration from a local dentist, Irving Sorkin, whose daughter Arleen was a Hollywood actress and passed it around, including to folks at HBO. Nearly 15 years later, Robert W. Cort produced the Emmy award winning 2004 HBO film Something the Lord Made. He told me he learned of Thomas when a writer friend sent him McCabe’s piece. Almost 20 years later, his film is still being seen by millions.

Helen realized after reading Thomas’s book that he helped develop cardiac surgery far more than she had appreciated, she told his widow, Clara Thomas. In a Feb. 21, 1986, condolence letter, she also said she admired Thomas for standing up for what is right and just, and “all the more” for quietly bringing it out in his book.

A doctor asked me recently what it was like for a white woman to work with a Black man in the 1940s and 50s. The 1944 first pathbreaking surgery Blalock designed and Thomas tested to save children with abnormal hearts (“blue babies” with Tetralogy of Fallot) was Helen’s idea. Helen visited Thomas in his laboratory likely only once, to explain at length her patients’ problems, and thereafter communicated with him through Blalock. They worked in different spheres, she in a patient clinic and he in the laboratory. After surgery on the heart exploded, I imagine them exchanging nods in hospital hallways or stopping to chat amicably. They had much in common. Both were underpaid and underappreciated. Both fought injustices. Helen welcomed the opportunity to work with people different from herself; half of the physicians she selected every year for her fellowship training program in children’s hearts came from foreign countries, some with underdeveloped health care systems. Her 1952 fellows included Georgia native Effie Ellis, a biologist and infant health specialist. Ellis was the first full-time African American doctor to work at Hopkins.

This time of year, as children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig prepared to join her family in Boston, her Baltimore living room windows and walls would be decorated with strings of glittery Christmas cards and photos from her patients.

They were her real family, Helen’s niece, Polly, told me.

Like most women doctors in her era, Helen chose not to marry. She wrote that while she didn’t have the satisfaction of raising children of her own, she was blessed with a multitude of nieces and nephews. She saw them mainly in summer, though, at the family’s home on Cape Cod. Helen had to leave her beloved family to study at the Johns Hopkins school of medicine, one of few science-oriented schools to accept women, and stayed in Baltimore for the one job offer that allowed her to treat patients.

Except for 1930, the year she came down with chicken pox and admitted herself to the infectious diseases ward in the children’s hospital, Helen always returned to her family in Boston for Christmas.

“I had a lovely Christmas with my two sisters,” she wrote a friend after one visit. “My sister Mary had real candles on her tree! Oh – I’d forgotten how lovely they were and what a different feel they give one – the true meaning of Christmas swept back over me – and of course, for both of us – the Christmas of our childhood.”

Light illuminates the darkest corner, so I suspect she meant hope, the theme of A Heart Afire, my newly released biography of Helen. The renewed hope that accompanies a birth. Without hope, there can be no change. Helen called it imagination, which when accompanied by a strategy and hard work leads to advances in science and art and I will add, politics. This was a paraphrase of one of her heroes, Ralph Waldo Emerson. The German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of my heroes, called it optimism even in the face of overwhelming darkness, a feeling of not wanting the other guy to win that inspires you to act no matter the odds. He was executed in a Nazi prison for his part in an attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler. He explains in Letters and Papers from Prison, but this time of year, I dip into his Christmas Sermons.

Helen took a job that no male classmate wanted, studying children destined to die from heart damage. Even women colleagues worried she was wasting her time. She never gave up. Like Emerson, she renewed her spirit by walking the woods near her house and observing nature. As she wrote in the 1960s to a grieving mother, it was by studying and re-studying the problems of dying children that “we learned to help so many.”

Helen’s grandniece Mary sent me this old photo of a family dinner, possibly Thanksgiving or Christmas. Helen is far right, looking elegant as usual.