Barbara Moreland, a cheery grandmother who runs her husband Gary’s plumbing business in rural West Virginia, still has the patient wrist band she wore in 1965 when surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital fixed her flawed heart.

Read more

Your Custom Text Here

Barbara Moreland, a cheery grandmother who runs her husband Gary’s plumbing business in rural West Virginia, still has the patient wrist band she wore in 1965 when surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital fixed her flawed heart.

Read more

Finding a source who once lived next door to your subject and took detailed notes on her childhood is every biographer’s dream. So it was with gratitude that I returned last week to the place where my dream came true.

The tiny village of Cotuit on Cape Cod is as tranquil as it is picturesque.

The summer home of pioneering children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig, Cotuit nurtured, sustained, and inspired Helen throughout her life. It also helped me tell her story (A Heart Afire, MIT Press, 2023.)

On Main Street where the Taussig family home once stood, cedar-shingled cottages nestled among tall pines still front the sea. You can still wake up to a symphony of birds and savor local tomatoes and peaches. The big sport – after borrowing books from the Cotuit Library and admiring Lucy Gibbons Morse’s paper-cutting designs in the historical society’s museum – is an outing in a Cotuit skiff. Families have raced these flat-bottomed wooden boats with oversized sails for over a century.

On a first visit a decade ago, I discovered the diaries of James Herbert Morse, poet, New York City schoolteacher, Lucy’s husband, and the Taussig family’s summer neighbor. Morse (1841-1923) spent his day in a hammock writing essays and jotting down his observations about the life and times of folks who summered here. The Morse barn was a gathering spot for oyster roasts, popcorn parties, and children’s theatre, including in 1913, a play featuring Helen and her sisters. The girls often stopped by Morse’s hammock with the news.

Maintained by Cotuit’s historical society, which hosted my talk about Helen last week, the Morse diaries shed light on the origins of Helen’s compassion, resilience, and courage. It was here she ran joyfully in the snow, recovered from her mother’s death, put out her first fire. Together with stories from Helen’s relatives and what I uncovered about the importance of Cotuit to Helen during her tenure as head of the children’s heart clinic at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, I knew it deserved a starring role in my biography.

It was fashionable in the early and mid-20th century for doctors to leave hot, muggy Baltimore in August for cooler climes. But in 1934, nearly broken by her relentless effort to save children with heart problems, Helen stayed In Cotuit for five months. During her recovery, she built a cottage of her own where she could regularly rest and repower. Soon afterward, she made her first diagnostic breakthrough. By 1944, she was in the operating room with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Hopkins when he performed the heart surgery that would make them famous.

That's me on left, with Helen's great nephew Bunker Henderson and his wife, Dita. Helen's cottage faced the beachfront behind us.

With Helen’s great nephew, George “Bunker” Henderson, and his wife, Dita Henderson, I revisited the shoreline in front of Helen’s cottage where he and his siblings once played. The spit of land and a deep channel where Helen swam disappeared in a hurricane. The cottage where she hosted patients, friends, and doctors from around the world has been replaced too, but a neighbor with one of similar vintage gave us a tour of his. With cedar walls and floors, wide windows onto the sea, a brick fireplace for reading and gathering, it exuded simplicity and calm. Another Cotuit resident, Hellie Swartwood, told me that as a college student 40 years this summer, she cooked for Helen, set her table, and otherwise helped her prepare for guests. Sometimes Helen invited her to join in the party.

Helen kept a strict schedule – early swim, work until noon, and play in the afternoon. Daily she phoned her office to check on and direct care for patients undergoing operations. Here she wrote her first important paper and edited her definitive book on problems of the heart. Helen wrote so many letters about patients to staff and colleagues using a Cotuit P.O Box address that it is fair to say that, in addition to being a pioneering doctor, she was a pioneer in the now fashionable work-from-home movement. In the late 1940s on her beach front, she even diagnosed a Cotuit boy with a complicated heart defect and sent him off to Boston for surgery.

A Cotuit cottage in the style of one Helen built herself in 1934.

That little boy, Palmer Q. (“Joe”) Bessey, grew up to be a distinguished surgeon and critical care expert and helped treat burn victims in New York on 9/11. A long-time summer resident of Cotuit, he died in March at age 79. It was my privilege to meet his wife, Sassy, and family here.

Helen lived for her patients. Like the abnormal hearts she studied that found new paths around blocked routes to the lungs, she had to work harder to overcome obstacles.

At critical moments, Cotuit provided extra oxygen.

Cotuit also figures in my favorite portrait of Helen, but that’s a story for another time.

It’s the 126th birthday of Helen Brooke Taussig (1898-1986), the humble children’s doctor who helped start heart surgery and used her fame to advocate for patients. So much of her work is ongoing: her 1938 plea that we systematically monitor children for high blood pressure is only catching on, and her campaign to protect us from unsafe drugs needs a reboot (17,000 deaths a year from legal opioids alone!) What of her work to cultivate and share beauty?

On a visit to her former gardens in Baltimore last week, I sniffed the delicate Bella Donna rose bushes she planted more than 70 years ago. Inspired by Helen, the current owners tend 50 rose bushes, 50 types of dahlias and about 80 varieties of daffodils – nearly twice Helen’s count. Helen famously timed her biannual doctor gatherings and lawn parties for maximum May bloom. Today she’d have to start three weeks early. Her work is not done, but her legacy continues. (More photos on my FB author page).

This time of year, as children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig prepared to join her family in Boston, her Baltimore living room windows and walls would be decorated with strings of glittery Christmas cards and photos from her patients.

They were her real family, Helen’s niece, Polly, told me.

Like most women doctors in her era, Helen chose not to marry. She wrote that while she didn’t have the satisfaction of raising children of her own, she was blessed with a multitude of nieces and nephews. She saw them mainly in summer, though, at the family’s home on Cape Cod. Helen had to leave her beloved family to study at the Johns Hopkins school of medicine, one of few science-oriented schools to accept women, and stayed in Baltimore for the one job offer that allowed her to treat patients.

Except for 1930, the year she came down with chicken pox and admitted herself to the infectious diseases ward in the children’s hospital, Helen always returned to her family in Boston for Christmas.

“I had a lovely Christmas with my two sisters,” she wrote a friend after one visit. “My sister Mary had real candles on her tree! Oh – I’d forgotten how lovely they were and what a different feel they give one – the true meaning of Christmas swept back over me – and of course, for both of us – the Christmas of our childhood.”

Light illuminates the darkest corner, so I suspect she meant hope, the theme of A Heart Afire, my newly released biography of Helen. The renewed hope that accompanies a birth. Without hope, there can be no change. Helen called it imagination, which when accompanied by a strategy and hard work leads to advances in science and art and I will add, politics. This was a paraphrase of one of her heroes, Ralph Waldo Emerson. The German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of my heroes, called it optimism even in the face of overwhelming darkness, a feeling of not wanting the other guy to win that inspires you to act no matter the odds. He was executed in a Nazi prison for his part in an attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler. He explains in Letters and Papers from Prison, but this time of year, I dip into his Christmas Sermons.

Helen took a job that no male classmate wanted, studying children destined to die from heart damage. Even women colleagues worried she was wasting her time. She never gave up. Like Emerson, she renewed her spirit by walking the woods near her house and observing nature. As she wrote in the 1960s to a grieving mother, it was by studying and re-studying the problems of dying children that “we learned to help so many.”

Helen’s grandniece Mary sent me this old photo of a family dinner, possibly Thanksgiving or Christmas. Helen is far right, looking elegant as usual.

Today is the birthday of Charlotte Ferencz (1921-2016), one of many stellar 20th Century female doctors and scientists who names are known mostly within their professions. She helps narrate my biography of the children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig, (A Heart Afire, MIT Press, 2023). The story begins in Charlotte’s living room.

She was at first a source who pointed me to other sources and helped interpret documents. But I soon recognized that as a witness to the rise of women in medicine and key events of Helen’s life, Charlotte was perfectly placed to frame Helen’s story. She agreed to play “a bit part” in the book after much cajoling. But in the history of women in medicine, her role is larger than life. One task she took on was to ensure that that history is accurate.

One of nine women in a class of 94 at McGill University School of Medicine, Charlotte arrived in Baltimore in 1949 on a fellowship to study in Helen’s world-famous children’s heart clinic at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Unable to obtain a suitable job in Canada, she returned to Baltimore in the mid-1950s to run Helen’s rhematic fever clinic. Her disappointments were many, but her accomplishments greater than most women in her generation. She became a full professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in two fields, epidemiology & preventive medicine in 1978 and, in 1985, pediatrics. She directed the first large-scale investigation into the causes of children’s heart defects.

Until the day in 2011 that I knocked on Charlotte’s door at Charlestown, a suburban Maryland retirement community, I had never met a female physician of grandmotherly age. They existed, but not in large numbers. Until this generation, to live in an era when women doctors were common, you would have to return to colonial times, when women took care of their families out of necessity.

Like Helen, who moved to Baltimore to study medicine because Harvard didn’t admit women, Charlotte had to leave her family to fulfill her ambition. She also faced sorrow in childhood, her life forever changed by war. Today I remember her gentle, scholarly, and fun-loving nature. But above all, she possessed in enormous measure a quality that allowed her and so many other women in her era to succeed: courage.

PS: Charlotte refused to sit for a professional photographer, hence the blurred image here, taken by a neighbor passing by Charlotte’s door.

Two women in science are about to become even more famous.

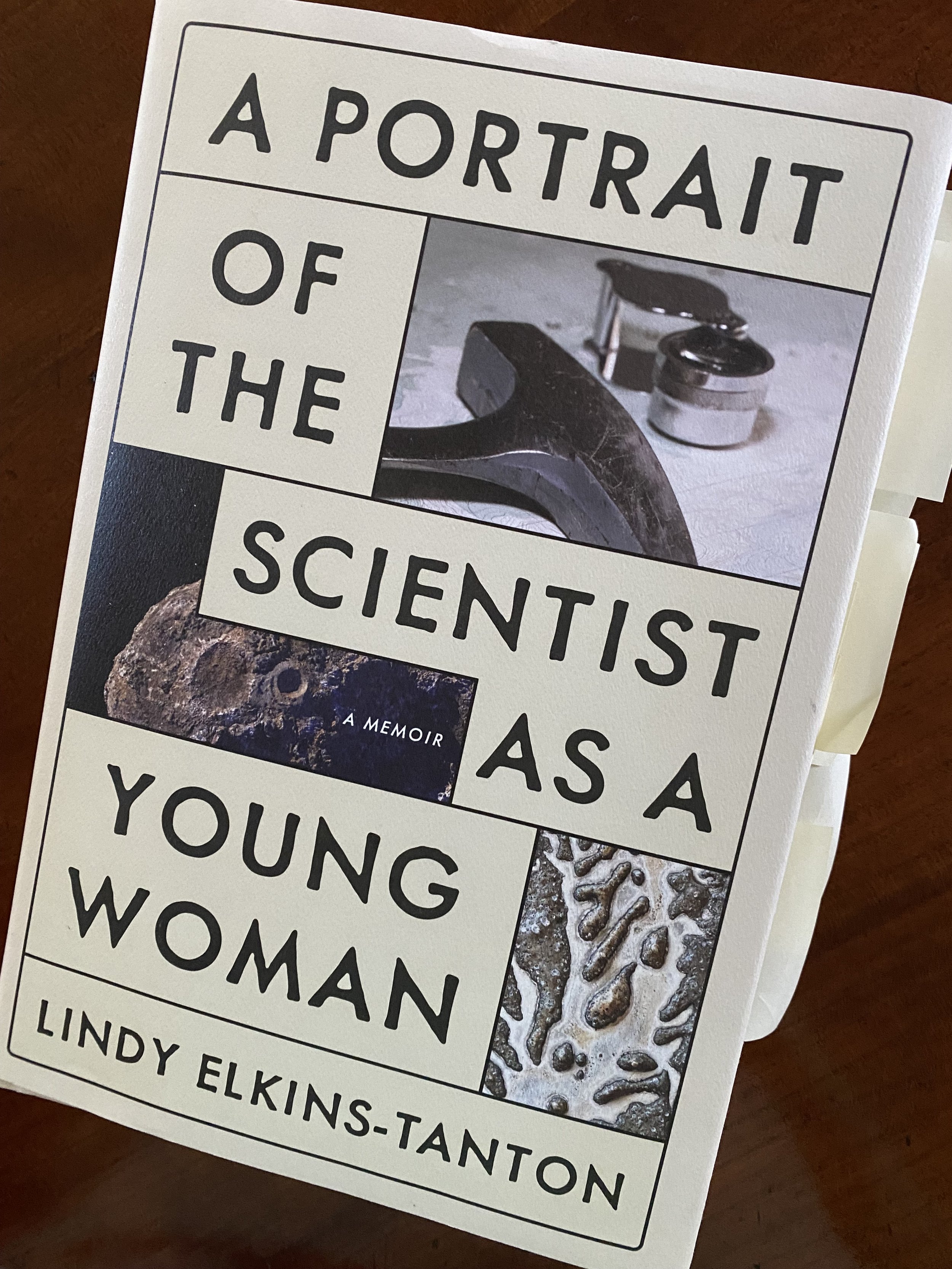

The fictional chemist Elizabeth Zott (Lessons in Chemistry), whose career is derailed by sexism, comes to Apple TV on Oct. 13. Her real-life counterpart, the planetary scientist Lindy Elkins-Tanton, leads an $800 million NASA mission to the asteroid Psyche that launches next Thursday, Oct. 5.

Their stories were published within weeks of each other. Since June 2022 when I spotted Elkins-Tanton’s memoire, Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Girl, in a Vero Beach, Fl., bookstore, I have been hyping her story to friends. The widely popular Lessons in Chemistry, No. 5 on the NYT bestseller list, is a rollicking tale, an indictment of sexism in higher education and an ode to science and love. The elegantly written Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Girl is that and much more, and I hope it will have a longer tail.

You cannot make this up. Like Zott, who winds up a TV cooking host when her advisor and rapist kicks her out of grad school, Elkins-Tanton detours from a science career, nagged by self-doubt despite earning a BS/MS in geology at MIT in four years. Teaching in a sleepy southern Maryland town, she confronts PTSD linked to childhood sexual attacks in woods near her home. Like Zott, she finds a love partner her equal. At 31 she returns to MIT for a Ph.D. Leads four field exhibitions to Alaska despite bad knees. Assembles an international team of scientists to collect hundreds of pounds of rocks in remote Siberian towns. Escapes a drunk Russian coal miner by stepping into a spa for a massage.

Chemists and physicists on her team calculate the temperature and pressure of sinking rock to confirm the process that leads to volcanic eruption, proving her idea about how molten rock formed and flooded Siberia. From particles on rocks, they link the eruption of gases like carbon monoxide to a mass extinction event 250 million years ago, a warning for our planet.

From rocks on earth, she moves to rocks in space. Gets her dream job at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration. Wins the NASA mission in 2015, just when she learns she has cancer, early stage.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton

Why forge ahead? Elkins-Tanton’s description of her pursuit of the unknown makes me want to join her team. It’s about the calm from working at the outer limits of knowledge, of going for the impossible. If Psyche is a piece of exploded planet, it might reveal what’s inside our own rocky planet. Or not. It might be rich enough in metal to supply Earth for ages. Or not. The liftoff might be grounded, as happened a year ago August, when NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab encountered a software problem. It will take three years for the spacecraft to get close enough to Psyche to collect data. No matter what happens, she writes, “if you are sure of your values and your vision, then every unit of work, every day of effort, is a real piece of progress and of value in itself.”

This sounds familiar! The children’s doctor whose story I tell in A Heart Afire, Helen Brooke Taussig’s Battle Against Defective Hearts, Unsafe Drugs, and Injustice in Medicine (MIT Press, Dec. 2023) mapped the inner workings of defective hearts knowing there was no treatment for dying children. “If the problem in which you are interested in is right, it is an objective and goal in itself,” Helen told an audience of women scientists in 1954. Eventually, following scientific methods, somebody would find the answer. As she did, with her idea for life-saving heart surgery.

In style, the graceful Elkins-Tanton is more like Helen than Zott. She takes small steps to topple what she calls the outdated “hero” model: the autocrat directing doctoral students and taking all the credit. She forces the ouster of a serial abuser and convinces her professional society to make abusive behavior a disqualifier for membership. Her team of bantering physicists, chemists, astronomers, and engineers is a model of the collaboration needed to tackle questions bigger than any one discipline. With her son and husband, she developed and is deploying a student-driven learning system to inspire the next generation of scientists.

Her motto: Change begins with questions.

Helen would agree. And the question we should be asking is not whether women can be scientists, as she told women professionals long ago, but what problems scientists should try to solve.

Change begins with questions.

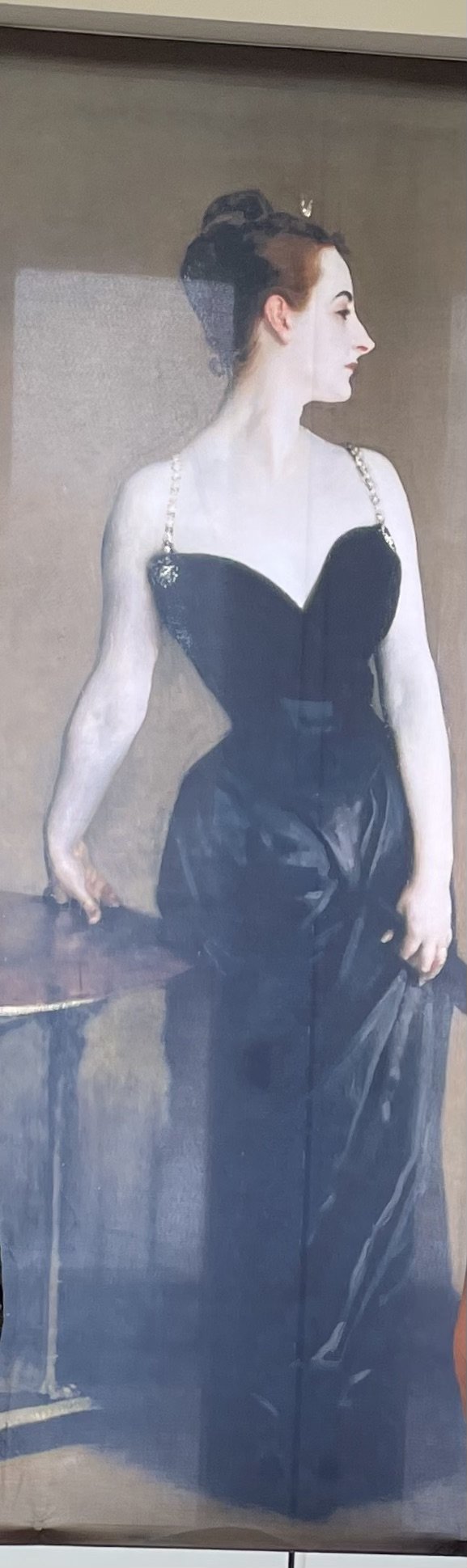

John Singer Sargent, the European-born American portrait artist, was a rising star in the Paris art world when he displayed an edgy, slightly decadent painting now known as Madame X at the Paris Salon in 1884. Parisians were horrified (if titillated) by the depiction of a society maven effortlessly flaunting her beauty; everyone recognized the subject, the married Amelie Gautreau, rumored to be an adulteress. As cultural historian Paul Fisher explains in The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World, (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2022), the painting forced Parisians to confront the “decadence in their midst” —truths they quietly tolerated but preferred not to acknowledge. Unnerved by the outrage, Sargent exiled himself to London.

Portraits and the relationship between artist and subject have long been an obsession, so I listened eagerly to Fisher talk recently about how Sargent pursued bold women to model for him as he built his reputation in Belle Epoque Paris. They were divas, dancers, iconoclasts, women who defied social norms and cultural constraints. Sargent admired his subjects’ daring and gives them noble attributes in his paintings, which is why Fisher said he likes Sargent so much.

Sargent’s women, painted in 1880-1890s Paris, hung from banners and flashed across flat screens during Fisher’s talk last month at the Hay-Adams Hotel in Washington, DC. The artist signals their fearlessness, their defiance, their power with the removal of a white glove, a darkness about the face, or in the original version of the famous Madame X, the strap of her evening gown falling from her shoulder. “Sargent’s women are not objects,” Fisher said, “Sargent saw women as people, which is why (his paintings) “are so gorgeous.”

Fisher dug into Sargent's life to find out the backstory of Sargent’s women. Who was the man behind these innovative portraits? Why was he was drawn to painting transgressions, sometimes highlighting secrets that his subjects may not have wanted revealed? In his stunning account of the “buttoned-up,” never-married artist, Fisher explores what was it like for a man of Sargent’s talents and sensibilities to move between high society and bohemian cultures in Europe at the turn of the 20th century. He details Sargent’s deep relationship with his sisters and other women as well as his male friendships to try to understand his subject’s sexuality in his time and because they influence his painting and choice of subject, which include male nudes and homoerotic scenes discovered after Sargent’s death. Fisher says Sargent painted bold women to work out what he could not do in his own life, “They are courageous enough to do the things he could not do…” he said.

Sargent hid Madame X in his studio for 20 years, when he restored her dress strap and sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He considered it one of his best portraits. Today the elegant and confident Madame X feels modern, like another long-hidden portrait I have seen, this one of Helen Brooke Taussig, a children’s doctor and the subject of my upcoming biography, (A Heart Afire, Helen Brooke Taussig’s Battle Against Defective Hearts, Unsafe Drugs, and Injustice in Medicine, MIT Press, Dec. 2023). It is stored in the archives of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

In May 1964, eighty years after Madame X’s disastrous debut, Helen’s portrait was unveiled to similar horror. Her blouse hangs slightly off her shoulder, oddly reminiscent of Madame X’s fallen strap. But it is her intense gaze that moved admirers to tears. Within days, the portrait was whisked away by doctors who hired the artist, Jamie Wyeth, not to be seen again for nearly 50 years, during which they battled repeatedly over whether it should ever be displayed and what it represented.

Why such an outcry over an image that today seems so realistic, even noble? I delved into Helen’s life to find out. Who was the woman whose honor they guarded? How had she endeared herself to so many? What were the social and cultural obstacles women doctors encountered in her era? At the time of the portrait?

One thing I learned was how tenaciously Helen pursued treatments for her patients. She never gave up. She was also gracious. Unlike the tearful Madame Gautreau, she did not fear her reputation would be ruined by a portrait, though she did suggest Wyeth give it a clandestine title: “Portrait of a Physician.”

A la Sargent’s Madame X in 1884, did Wyeth’s “Portrait of a Physician” in 1964 reveal a secret about Helen too unseemly to acknowledge in public? Too ahead of its time?

What should powerful women look like?

And who decides?