Barbara Moreland, a cheery grandmother who runs her husband Gary’s plumbing business in rural West Virginia, still has the patient wrist band she wore in 1965 when surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital fixed her flawed heart.

Read more

Your Custom Text Here

Barbara Moreland, a cheery grandmother who runs her husband Gary’s plumbing business in rural West Virginia, still has the patient wrist band she wore in 1965 when surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital fixed her flawed heart.

Read more

Finding a source who once lived next door to your subject and took detailed notes on her childhood is every biographer’s dream. So it was with gratitude that I returned last week to the place where my dream came true.

The tiny village of Cotuit on Cape Cod is as tranquil as it is picturesque.

The summer home of pioneering children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig, Cotuit nurtured, sustained, and inspired Helen throughout her life. It also helped me tell her story (A Heart Afire, MIT Press, 2023.)

On Main Street where the Taussig family home once stood, cedar-shingled cottages nestled among tall pines still front the sea. You can still wake up to a symphony of birds and savor local tomatoes and peaches. The big sport – after borrowing books from the Cotuit Library and admiring Lucy Gibbons Morse’s paper-cutting designs in the historical society’s museum – is an outing in a Cotuit skiff. Families have raced these flat-bottomed wooden boats with oversized sails for over a century.

On a first visit a decade ago, I discovered the diaries of James Herbert Morse, poet, New York City schoolteacher, Lucy’s husband, and the Taussig family’s summer neighbor. Morse (1841-1923) spent his day in a hammock writing essays and jotting down his observations about the life and times of folks who summered here. The Morse barn was a gathering spot for oyster roasts, popcorn parties, and children’s theatre, including in 1913, a play featuring Helen and her sisters. The girls often stopped by Morse’s hammock with the news.

Maintained by Cotuit’s historical society, which hosted my talk about Helen last week, the Morse diaries shed light on the origins of Helen’s compassion, resilience, and courage. It was here she ran joyfully in the snow, recovered from her mother’s death, put out her first fire. Together with stories from Helen’s relatives and what I uncovered about the importance of Cotuit to Helen during her tenure as head of the children’s heart clinic at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, I knew it deserved a starring role in my biography.

It was fashionable in the early and mid-20th century for doctors to leave hot, muggy Baltimore in August for cooler climes. But in 1934, nearly broken by her relentless effort to save children with heart problems, Helen stayed In Cotuit for five months. During her recovery, she built a cottage of her own where she could regularly rest and repower. Soon afterward, she made her first diagnostic breakthrough. By 1944, she was in the operating room with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Hopkins when he performed the heart surgery that would make them famous.

That's me on left, with Helen's great nephew Bunker Henderson and his wife, Dita. Helen's cottage faced the beachfront behind us.

With Helen’s great nephew, George “Bunker” Henderson, and his wife, Dita Henderson, I revisited the shoreline in front of Helen’s cottage where he and his siblings once played. The spit of land and a deep channel where Helen swam disappeared in a hurricane. The cottage where she hosted patients, friends, and doctors from around the world has been replaced too, but a neighbor with one of similar vintage gave us a tour of his. With cedar walls and floors, wide windows onto the sea, a brick fireplace for reading and gathering, it exuded simplicity and calm. Another Cotuit resident, Hellie Swartwood, told me that as a college student 40 years this summer, she cooked for Helen, set her table, and otherwise helped her prepare for guests. Sometimes Helen invited her to join in the party.

Helen kept a strict schedule – early swim, work until noon, and play in the afternoon. Daily she phoned her office to check on and direct care for patients undergoing operations. Here she wrote her first important paper and edited her definitive book on problems of the heart. Helen wrote so many letters about patients to staff and colleagues using a Cotuit P.O Box address that it is fair to say that, in addition to being a pioneering doctor, she was a pioneer in the now fashionable work-from-home movement. In the late 1940s on her beach front, she even diagnosed a Cotuit boy with a complicated heart defect and sent him off to Boston for surgery.

A Cotuit cottage in the style of one Helen built herself in 1934.

That little boy, Palmer Q. (“Joe”) Bessey, grew up to be a distinguished surgeon and critical care expert and helped treat burn victims in New York on 9/11. A long-time summer resident of Cotuit, he died in March at age 79. It was my privilege to meet his wife, Sassy, and family here.

Helen lived for her patients. Like the abnormal hearts she studied that found new paths around blocked routes to the lungs, she had to work harder to overcome obstacles.

At critical moments, Cotuit provided extra oxygen.

Cotuit also figures in my favorite portrait of Helen, but that’s a story for another time.

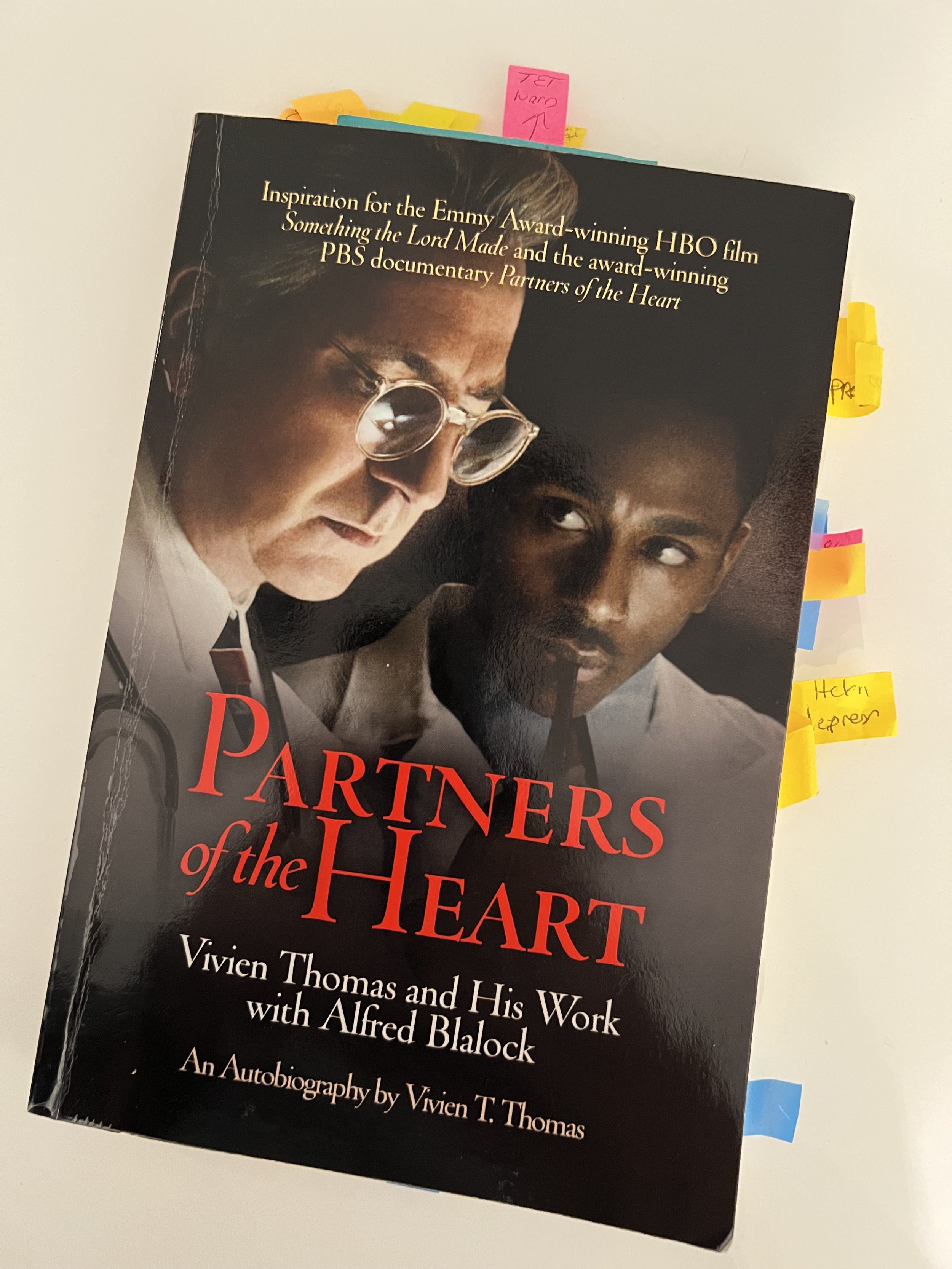

Thanks to a December Baltimore Banner article by Leslie Gray Streeter about the popularity on TikTok and YouTube of Vivien Thomas, the self-taught pioneering African American surgeon, Baltimoreans are discovering and re-discovering the 2004 HBO movie about his life, Something the Lord Made.

A friend who saw the movie for the first time asked if I had known of it, since my book, A Heart Afire, a biography of the pediatrician Helen Brooke Taussig, details some of Thomas’s work at Johns Hopkins hospital with the surgeon Alfred Blalock to develop lifesaving heart surgery for her patients.

Yes! The movie was based in part on Thomas’s 1985 memoire, a source I consulted to learn about the surgery and Helen’s role in it. It’s an eclectic take on history: blow-by-blow details of laboratory experiments and techniques, chatty sketches of famous surgeons, and straightforward tales of indignities suffered by a self-made Black man.

It was a book Thomas never expected to write. A publisher was hard to find. And with the original title of Pioneering Research in Surgical Shock and Cardiovascular Surgery, the audience was limited.

How did Vivien Thomas win his place in history and popular culture?

e.

A top surgeon at Hopkins realized the importance and extent of Vivien Thomas’s work while researching Blalock’s life and pushed Thomas to write his autobiography. Mark M. Ravitch, an outsized personality who helped develop pediatric surgery, kept after Thomas for nearly two decades after learning, to his surprise, that Blalock delegated his experimental work on the nature of traumatic shock to Thomas and a surgical resident. At the time, it was customary for surgeons to perform their own experiments. Neither Thomas’s name nor his contribution was noted on papers Blalock wrote about his pioneering discovery, which made surgery safer.

Ravitch was also chagrinned to learn that he himself mistakenly credited another surgeon, C. Rollins Hanlon, with an innovative surgery Thomas developed. This was first surgical treatment to help children born with their major arteries reversed (transposition of the great arteries). Hanlon and Blalock are listed as authors on the 1948 paper describing it. Thomas had embarked on his solution for this condition secretly, testing it again and again in dogs before unveiling it to Blalock. (Usually, Blalock directed and the two improved on the idea.) When he showed Blalock the opening he created between the upper heart and a pulmonary vein — a new path that allowed oxygenated blood to flow into the body — Blalock reacted with disbelief. It looks “like something the Lord made,” Blalock said. (Hanlon also played a key role in this surgery; his refinements dramatically reduced mortality.)

While Thomas worked a second job tending bar to pay his bills and wondered whether his life story was worth telling, Ravitch and other surgeons in Blalock’s famed training program – many of whom learned to operate in Thomas’s dog lab -- commissioned a portrait of him to hang in the medical school. It was unveiled in 1971. In 1976, Hopkins awarded him an honorary degree and made him an official member of the faculty.

After he retired in 1979, Thomas began writing his account longhand using his extensive lab records. Ravitch pushed Thomas to provide more detail about the people he named and his own impressions. Thomas added this without judgment. (In one memorable scene, Thomas prepared to quit after Blalock angrily dressed him down, leading Blalock to promise never again to speak to Thomas in raised voice.)

To help with what an ailing Thomas called his “production problem,” Ravitch assembled and ordered Thomas’s chapters and handwritten scenes, and wrote the index. A few days before his book was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in December 1985, Thomas died. Ravitch went into high gear, pitching the memoire with ferocity, as is evident from Ravitch’s papers archived at the National Library of Medicine. He mailed the book or letters about it to everyone on his Rolodex (he was a past president of the American Surgical Association.) It was his colleague Judson G. Randolph, a George Washington University surgeon, chief of Washington’s Children’s Hospital, and Ravitch’s co-author on a pediatric surgery textbook, who told writer Katie McCabe about Thomas.

McCabe tried for four years to sell a story about Thomas before Washingtonian published it in 1989. By then, Ravitch was dead. Her article won the 1990 National Magazine Award and admiration from a local dentist, Irving Sorkin, whose daughter Arleen was a Hollywood actress and passed it around, including to folks at HBO. Nearly 15 years later, Robert W. Cort produced the Emmy award winning 2004 HBO film Something the Lord Made. He told me he learned of Thomas when a writer friend sent him McCabe’s piece. Almost 20 years later, his film is still being seen by millions.

Helen realized after reading Thomas’s book that he helped develop cardiac surgery far more than she had appreciated, she told his widow, Clara Thomas. In a Feb. 21, 1986, condolence letter, she also said she admired Thomas for standing up for what is right and just, and “all the more” for quietly bringing it out in his book.

A doctor asked me recently what it was like for a white woman to work with a Black man in the 1940s and 50s. The 1944 first pathbreaking surgery Blalock designed and Thomas tested to save children with abnormal hearts (“blue babies” with Tetralogy of Fallot) was Helen’s idea. Helen visited Thomas in his laboratory likely only once, to explain at length her patients’ problems, and thereafter communicated with him through Blalock. They worked in different spheres, she in a patient clinic and he in the laboratory. After surgery on the heart exploded, I imagine them exchanging nods in hospital hallways or stopping to chat amicably. They had much in common. Both were underpaid and underappreciated. Both fought injustices. Helen welcomed the opportunity to work with people different from herself; half of the physicians she selected every year for her fellowship training program in children’s hearts came from foreign countries, some with underdeveloped health care systems. Her 1952 fellows included Georgia native Effie Ellis, a biologist and infant health specialist. Ellis was the first full-time African American doctor to work at Hopkins.