Finding a source who once lived next door to your subject and took detailed notes on her childhood is every biographer’s dream. So it was with gratitude that I returned last week to the place where my dream came true.

The tiny village of Cotuit on Cape Cod is as tranquil as it is picturesque.

The summer home of pioneering children’s doctor Helen Brooke Taussig, Cotuit nurtured, sustained, and inspired Helen throughout her life. It also helped me tell her story (A Heart Afire, MIT Press, 2023.)

On Main Street where the Taussig family home once stood, cedar-shingled cottages nestled among tall pines still front the sea. You can still wake up to a symphony of birds and savor local tomatoes and peaches. The big sport – after borrowing books from the Cotuit Library and admiring Lucy Gibbons Morse’s paper-cutting designs in the historical society’s museum – is an outing in a Cotuit skiff. Families have raced these flat-bottomed wooden boats with oversized sails for over a century.

On a first visit a decade ago, I discovered the diaries of James Herbert Morse, poet, New York City schoolteacher, Lucy’s husband, and the Taussig family’s summer neighbor. Morse (1841-1923) spent his day in a hammock writing essays and jotting down his observations about the life and times of folks who summered here. The Morse barn was a gathering spot for oyster roasts, popcorn parties, and children’s theatre, including in 1913, a play featuring Helen and her sisters. The girls often stopped by Morse’s hammock with the news.

Maintained by Cotuit’s historical society, which hosted my talk about Helen last week, the Morse diaries shed light on the origins of Helen’s compassion, resilience, and courage. It was here she ran joyfully in the snow, recovered from her mother’s death, put out her first fire. Together with stories from Helen’s relatives and what I uncovered about the importance of Cotuit to Helen during her tenure as head of the children’s heart clinic at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, I knew it deserved a starring role in my biography.

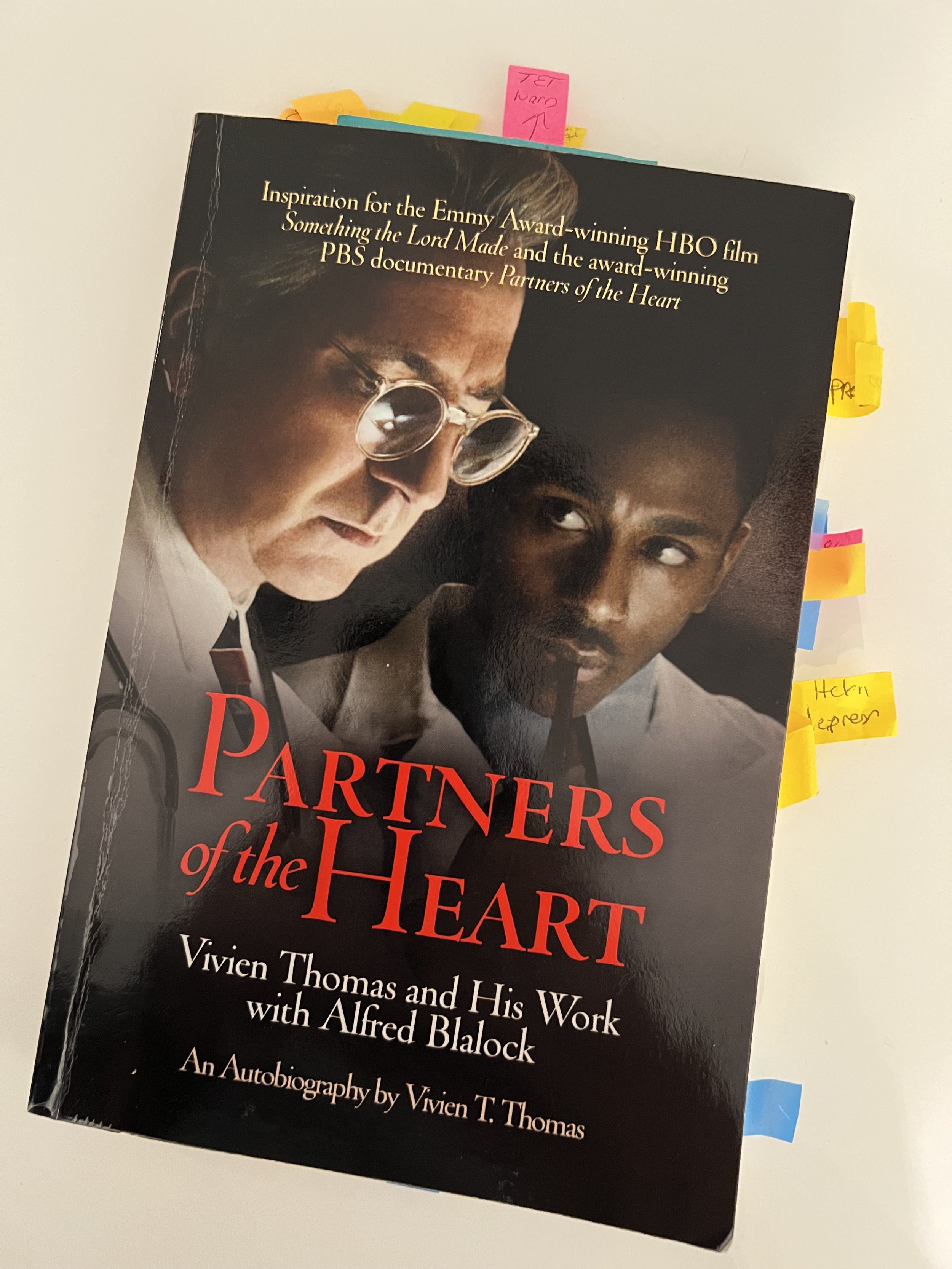

It was fashionable in the early and mid-20th century for doctors to leave hot, muggy Baltimore in August for cooler climes. But in 1934, nearly broken by her relentless effort to save children with heart problems, Helen stayed In Cotuit for five months. During her recovery, she built a cottage of her own where she could regularly rest and repower. Soon afterward, she made her first diagnostic breakthrough. By 1944, she was in the operating room with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Hopkins when he performed the heart surgery that would make them famous.

That's me on left, with Helen's great nephew Bunker Henderson and his wife, Dita. Helen's cottage faced the beachfront behind us.

With Helen’s great nephew, George “Bunker” Henderson, and his wife, Dita Henderson, I revisited the shoreline in front of Helen’s cottage where he and his siblings once played. The spit of land and a deep channel where Helen swam disappeared in a hurricane. The cottage where she hosted patients, friends, and doctors from around the world has been replaced too, but a neighbor with one of similar vintage gave us a tour of his. With cedar walls and floors, wide windows onto the sea, a brick fireplace for reading and gathering, it exuded simplicity and calm. Another Cotuit resident, Hellie Swartwood, told me that as a college student 40 years this summer, she cooked for Helen, set her table, and otherwise helped her prepare for guests. Sometimes Helen invited her to join in the party.

Helen kept a strict schedule – early swim, work until noon, and play in the afternoon. Daily she phoned her office to check on and direct care for patients undergoing operations. Here she wrote her first important paper and edited her definitive book on problems of the heart. Helen wrote so many letters about patients to staff and colleagues using a Cotuit P.O Box address that it is fair to say that, in addition to being a pioneering doctor, she was a pioneer in the now fashionable work-from-home movement. In the late 1940s on her beach front, she even diagnosed a Cotuit boy with a complicated heart defect and sent him off to Boston for surgery.

A Cotuit cottage in the style of one Helen built herself in 1934.

That little boy, Palmer Q. (“Joe”) Bessey, grew up to be a distinguished surgeon and critical care expert and helped treat burn victims in New York on 9/11. A long-time summer resident of Cotuit, he died in March at age 79. It was my privilege to meet his wife, Sassy, and family here.

Helen lived for her patients. Like the abnormal hearts she studied that found new paths around blocked routes to the lungs, she had to work harder to overcome obstacles.

At critical moments, Cotuit provided extra oxygen.

Cotuit also figures in my favorite portrait of Helen, but that’s a story for another time.